By Alonna Carter-Donaldson

Note: Throughout the article the word “deaf” has been represented as capitalized to represent a group of people who identify as a member of the Deaf culture, while the lower case “d” in the word “deaf” or “deaf and hard of hearing” represents an individual who is part of the community.

“In the summer of the year 1868 a little deaf and dumb colored boy was brought to the Mission Sabbath School connected with the Third United Presbyterian church, Pittsburgh, Pa. As the child seemed bright and active, the Superintendent, Mr. Joel Kerr, took a deep interest in his welfare.” – History of the Western Pennsylvania Institution for the Instruction of the Dumb and Deaf from its Origin in the Year 1869 (published 1911)

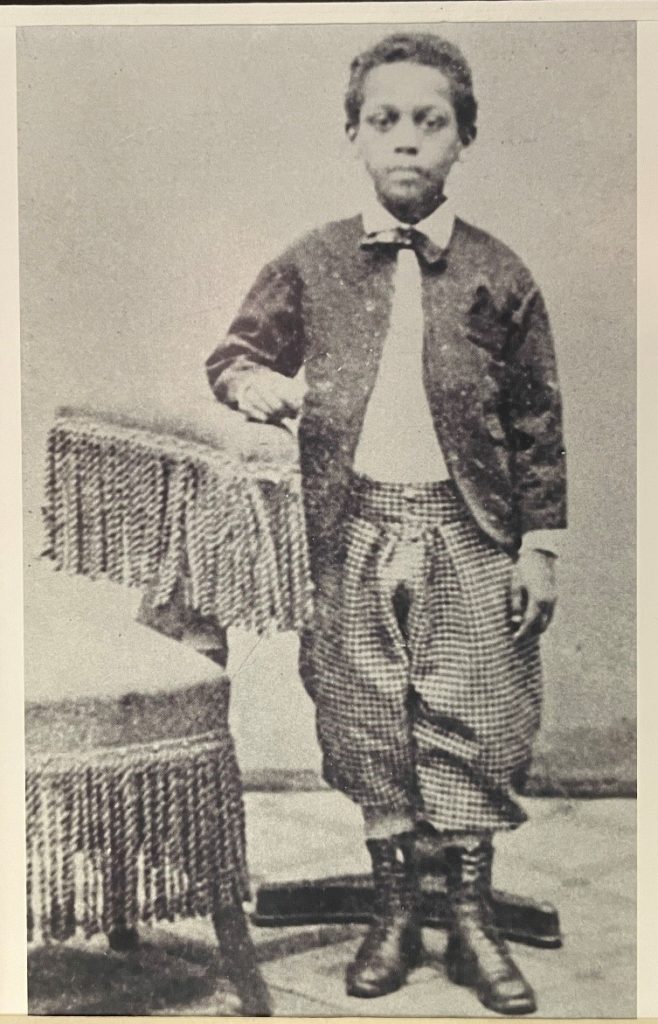

This paragraph, from a history of the school now known as the Western Pennsylvania School for the Deaf, is referring to Henry Collins Bell, its first student.

Henry Collins Bell was born in 1862 to Robert W. Bell and Martha Caroline Bell. His father Robert was born in Pennsylvania and worked as a porter, while his mother Martha, also known as Caroline in some records, was born in Arkansas. It is not known how Caroline came to Pittsburgh or whether she was free or enslaved in Arkansas, though one might assume the latter. The family resided at various residences in Pittsburgh’s Hill District and the South Side, once at 67 Roberts Street.

Deaf education in the 1800’s for children, and particularly Black children, was not widespread. African American children were lucky if they could find any public school in the city of Pittsburgh near their homes due to the Common School Law of 1854 which allowed separate schools for Black and white children in Pennsylvania. Many African American children were taught in church basements and office building spaces that were rented out; education for children with disabilities would have taken place in the church if it had taken place at all.

When Henry C. Bell entered the Third Presbyterian Church on a Sunday in 1868, he was not only defying racial order which would have remanded him to a Black Sabbath Day school, but he was also about to making history for Deaf education in the city of Pittsburgh.

Henry came to the class accompanied by a young German boy who was rewarded for bringing new pupils to school. Superintendent Kerr was curious about the Black child who entered his classroom and attempted to greet him, but Henry did not answer. When Kerr questioned why child was not at the “colored” Sabbath Day School in the next building over, the German boy responded, “His tongue is tied, and his ears are stopped up, and he can’t learn nothing there.”

Kerr allowed Henry to stay in the class that day. However, Henry’s way of communicating through facial expressions was seen as a disruption, and made the other children laugh. Kerr decided that Henry should go home.

This did not deter Henry; the next Sunday Henry came back – through a window – and stayed until Kerr again dismissed him. This cycle would repeat each week until a teacher, impressed by Henry’s tenacity, convinced Kerr to hire her cousin William Drum, who was also deaf, to teach Henry. Drum, seeing an opportunity for the school to help many children, encouraged Kerr to find other Deaf children in the city so that they also could be taught in groups.

Drum’s instruction was impactful with Henry. An 1869 article in the Pittsburgh Daily Post stated that in 27 lessons Henry learned the alphabet, printed his name, and communicated with sign language. The school also flourished and as word spread about the new school throughout Western Pennsylvania, the school became residential in addition to being a day school, so that students who lived far away could attend without having to travel long distances.

In 1870, James Kelly, Esq, a wealthy citizen of Wilkins Township, proposed a gift of 10 acres of land for the school to build a larger location near the Edgewood Railroad Station. However, due to a lawsuit between the school and the railroad company over who owned the property, the school would move to many locations including Wylie Avenue in the Hill District, and a hotel in Turtle Creek where Henry would also move to, before it was finally able to open in Edgewood on October 1, 1884.

Though Henry progressed in his education, he was not immune to the pervasive racism of the time. When Drum began teaching Henry’s class, a white woman threatened to pull her child out because she did not want him in the same class with a Black student. The school hired an additional teacher to teach the children whose parents objected to integrated education.

In 1879, another student was physically abused by a teacher and Henry testified to the Board of Directors after he saw bruise marks on his classmate. Even though Henry’s testimony was not delivered in a court of law, Henry could have faced enormous obstacles in speaking up, as biases of the time would have suggested that Henry should not be believed. In fact, while Henry testified to the Board of Directors about what he seen, the accused teacher said, “I don’t think the boy understands the questions.” Yet Henry did not allow the defendants opinion to stop him from speaking the truth of what he saw. Thanks in part to his testimony, the teacher was arrested for his harsh discipline.

After graduating from the school in 1880, Henry returned home to the Hill District to live with his parents and then moved to the South Side where he obtained work as a wire drawer, where he made wire by pulling a metal rod through small holes to be used in machinery.

In the mid-1880’s, Henry returned to the Edgewood area where his alma mater was located and worked as a carpenter. In the early 1890’s, he relocated to Wellsville, Ohio, and became a barber. He is mentioned in the August 18, 1892, Deaf Mute Journal as visiting Gallaudet University in Washington, DC before he returned to Pittsburgh to visit his uncle.

Sadly, Henry passed away in Wellsville (sometimes referred to as Wellsburg), Ohio, after being ill for a week, at the age of thirty. Henry had also only been married for two weeks before succumbing to this illness.

While Henry did not live to see the full impact of his persistence, he created an enduring legacy in the fight for deaf and hard-of-hearing education in Western Pennsylvania. Henry’s self-advocacy laid the groundwork for future Deaf education advocates. Brandi Lee is one of those advocates, in addition being an author and a mother who lives on the Northside of Pittsburgh. Lee is a student at Carlow University where she is studying to receive a BA in Social Work. She is also a volunteer for Cochlear Americas, a cochlear implant manufacturer and a Community Health Advocate who advocates for African American mothers in the Pittsburgh community. Lee identifies as deaf and hard of hearing.

Lee said that she sees some of her own story in Henry Bell’s. “There is something about the need to be resilient and to kind of push when you are an African American with a disability,” she explained. “He really pushed to make sure that he got an education. And now it has impacted thousands of children year by year. So that is just so important and helpful for me to remember because sometimes I feel like I am not doing enough.”

Asked what social justice groups could do to better partner with those in the disability community, Lee said “One thing that can be done [is to ask] Do you have captions? Is there an interpreter? Is this videotaped or streamed live, so that I can watch it in an isolated environment where I have control over the noise around me and engage in the content?”

Lee also had some further words of wisdom: “I would like people to know that deafness, hearing loss, and any disability is dynamic. We get stuck on the disability part, the handicapped part, the inability part, and we forget that when you lose a sense, your other senses are heightened. Let your support and someone else be a bridge so that not only they can get the resources and connection they need but you can get the resources and connection you need from them. It benefits all of us to communicate with respect.”